Exercise 1

A. Listen to the radio program and complete the summary.

In this new book, Outliers, Gladwell argues that Beethoven, the Beatles and Bill Gates all have one thing in 1______. They 2______ what they do, and they practiced a lot. In fact, Gladwell discovered that, in order to be truly 3______ in anything, it is necessary to practice for more than 4______ hours. These people have done that, which is why he believes they have been so 5______.

B. Listen again. Are the statements true (T) or false (F)?

1 If we want to learn from Bill Gates’ achievements, we need to look at where he came from and the opportunities he had.

2 If you’re going to be world-class at something, you need to have parents who are high achievers.

3 The Beatles played all-night concerts in Hamburg, and this helped them to master their craft.

4 To become a successful tennis player, you need a very talented teacher and enough money to pay for your lessons.

Answer & Audioscript

A

1 common 2 practiced 3 world-class 4 10,000 5 successful

B

1 T 2 F 3 T 4 F

Audioscript

H = Host I = Ian

P: Hello, and welcome back to the Focus podcast. I’m Jenni Osman, the editor of Focus, the monthly science and technology magazine. He’s the hugely influential author of Blink and The Tipping Point. His work is quoted by academics, presidents and your buddies at work. And now Malcolm Gladwell has turned that deft mind of his to a new subject: the science of success. In his new book, Outliers, Gladwell argues that, if we want to be successful, we should think less about what successful people are like and more about where they have come from and the opportunities they have had along the way. Now, Ian’s read the book, and he joins me. Now … his new book is looking at success …

I: Yes, and what he says is, erm, that, if we think about somebody like Bill Gates, a hugely successful person, and we want to learn from, his achievements, then what do we look at? We look at what that man is like, you know, what drives him; what does he do on a day-to-day basis; how can we be more like him? But, what Gladwell argues in the new book is, is that we should pay less attention to that side of things and look at where Bill Gates came from. So, how did he get to where he got to, the opportunities he had along the way. And, what he says is that Bill Gates has one thing in common with another group of very successful people, the Beatles.

H: So, what’s that?

I: Well, they both practiced what they do, and they practiced a lot.

H: Right, so how much is a lot?

I: A lot is ten thousand hours. That’s like the magic number if you’re going to become world-class at anything in the world. You need to put ten thousand hours’ practice in.

H: Oh, OK.

I: So, the Beatles, they, they were doing gigs, you know, like all-night gigs in Hamburg, in these little clubs, and just the number of hours that they put in on the stage, allowed them to master their craft …

H: I think the ten thousand hours magic number is really interesting because, as you know, I used to play tennis professionally, and I hit a load of tennis balls when I was younger. And I’m sure, I must have done ten thousand hours’ worth, you know. I must have done four hours a day and stuff. And I remember speaking to Martina Hingis’ mom about why she thought her kid was so good, such a prodigy. She basically said, “My daughter has been hitting tennis balls since the age of three, and she has hit X number of tennis balls for X number of hours, and it’s, you know, I’m sure she’s …” So once you’re over that magic number of ten thousand … yeah.

I: The same goes for people like Beethoven … It’s incredible how …

H: But, at the end of the day, you have to have talent.

I: You have to have raw talent; you have to have belief in what you can do; and you have to have the will to put those hours in … but you also need the opportunity.

H: Uh huh.

Exercise 2

A. Listen. Check (✓) the things in the box they talk about.

|

names – faces – dates – words – birthdays – directions to places – books you’ve read – places – movies – information about products – things that happened to you when you were very young – jokes |

B. Read the notes about Peggy. Listen again and use the same headings to write notes about John and Tim.

PEGGY

Job – sales rep 4 publishing company

Memory – needs 2 remember lots not good at directions; used to get lost all the time.

has to remember names faces of people + product information

Answer & Audioscript

A

names, faces, dates, words, birthdays, directions to places, films, information about products, jokes

B

JOHN:

Job: Actor

Memory: needs 2 remember lines (words) & “blocking” (where 2 stand or move), bad at birthdays & dates

TIM:

Job: history student

Memory: needs 2 remember dates & names, bad at jokes & movies

Audioscript

T = Tim P = Peggy J = John

T: So what about your memory, Peggy? How good is it?

P: It’s OK, which is lucky ’cause I need to remember lots of things.

J: Like what?

P: Well, I’m a sales rep for a publishing company, so I’m usually out visiting schools, trying to sell books.

J: So you need to remember … what exactly?

P: Oh, lots of things. The worst thing when I started was just trying to remember how to get to these schools in my car. I used to get lost all the time. I’m not very good at directions. Then, once you’re there, you have to remember the names and faces of the people you’re talking to. I once spent a whole hour calling this woman Sally when her name was Samantha.

T: And she didn’t tell you?

P: For some reason she didn’t tell me. And then there’s all the product information.

J: Product information? What, the books?

P: Yes. We sell about five hundred different books, and I have to know about all of them. I mean, it gets easier, thank goodness, but I still make mistakes occasionally. What about you, John? You’re an actor, right?

J: Yeah. The main thing I have to remember is my lines. Fortunately, I have a good memory for words, and I don’t find it that hard to memorize them. So, I mean, yeah. The other thing you have to remember when you’re in the theater is the blocking.

T: What’s that?

J: Blocking? It’s where you stand or move to, you know? Like, when you say your words, you might have to walk quickly across the stage or move in front of someone. It’s all planned and, you have to remember it.

T: Oh, I see.

J: But it’s funny: for, for other things I have a terrible memory. I’m totally useless. I always forget birthdays and dates. I’m always late for things. It’s just … luckily, I’m OK with my lines.

P: What about you, Tim?

T: I’m probably the same as all other students, at least all other history students. I have to memorize dates and also names. But it’s not that difficult because you read about them so much you can’t really forget them. But, for other things, I have a really bad memory. I can never remember jokes or movies. Sometimes I’m watching a movie and, after an hour, I realize I’ve seen it already. I’m completely hopeless like that.

J: Oh, me, too …

Exercise 3

A. Listen to two people discussing intelligence. What do they talk about?

a) intelligent animals

b) intelligent people

c) “intelligent” technology

B. Listen again and answer the questions.

1 Why does the man think the boy from Egypt is intelligent?

2 Why does he think his friend is intelligent? What did the friend do?

3 Why are degrees and certificates useful according to the woman?

4 What else, according to the woman, gives you an education?

Answer & Audioscript

A

b) intelligent people

B

1 The boy can sell you something in about fifteen languages.

He guesses where you’re from, and then he starts speaking your language.

2 The friend built his own house. He taught himself how to do it.

3 They show that you’re able and motivated enough to complete a course of study.

4 Real life experience, traveling and meeting people also give you an education.

Audioscript

A: It’s interesting. One of the most intelligent people I know is a ten-year-old boy from Egypt. He doesn’t go to school, and he works in a touristy area in Cairo. And he sells things to tourists, little souvenirs. Now, the reason I say he’s intelligent is that he can sell you something in about fifteen languages. I once spent an afternoon watching him, and it was incredible. Most of the time he uses English, but he guesses where you’re from, and then he starts speaking your language. For example, he can speak a little bit of French, Spanish, Japanese, Italian, etc. It’s amazing. He knows enough in all these languages to say “hello” and sell you something.

B: How did he learn the languages?

A: I asked him that, and he said he learned them by talking to tourists.

B: That’s amazing. Just talking to people, you can learn so much.

A: So, like I said, he doesn’t go to school, but, for me, he’s super-intelligent. Let me give you another example. I have a friend who built his own house. He just taught himself how to do it: bought some land, bought the materials and the equipment and just did it. No qualifications—no certificates, no college degree.

B: In my view, that’s impressive. I couldn’t do that.

A: This is someone who left school at fifteen to do an apprenticeship.

B: Degrees and certificates aren’t everything, but, you know, having said that, I do think they are useful in some ways. For one thing, they show that you’re able to complete a course of study—that you’re motivated enough.

A: Yeah, I think that’s true.

B: But I must say real life experience, traveling and meeting people … these give you an amazing education, too.

A: Exactly. That’s what I was saying. Like the boy from Egypt.

Exercise 4

A. Listen to someone talking about a recent challenge/achievement. Answer the questions.

1 What was her challenge?

2 Was it a good or bad experience?

3 What did she find easy?

4 What problem(s) did she have?

5 Did she succeed?

Answer & Audioscript

1 To learn how to scuba dive.

2 It was a really good experience.

3 The classroom/theoretical training.

4 The practical stuff: she was very nervous, the water was freezing, she had trouble going under the water and her ears got blocked up.

5 Yes, she managed to do it eventually.

Audioscript

A couple of years ago, I learned how to scuba dive, which was, really exciting, really good experience. And, when you’re learning, half of the, the training is in the classroom, and half is, uh, practice in a swimming pool. So the classroom stuff was fine. I found it really quite easy. I was learning with my mom, and she was really worried about doing the kind of more academic stuff and passing the test. But, I found that part OK. It was the practical stuff that I had trouble with, and she was really lucky, she was really good. But you go and you learn all the technical stuff, you know, how to go underwater, how to clear your mask if you get water in it, and so on. And then you have to do two dives outside in a, in a kind of reservoir or a quarry or, you know, something like that. But obviously, because I’m in Canada, it was really, really cold. And we woke up on the morning of our dive, and there was ice on the water. So, when we got there, we were very nervous and didn’t want to get into the water. But, once I was in, it was so freezing that I tried to go under the water. But, the more I tried, the harder it got. And then I got very frustrated and started to cry, and then all my ears got blocked up, and I couldn’t get under. But eventually I managed to do it and went down, passed my test, did all of the skills that you need to do. Despite the fact that I was so terrible at it, I managed to pass. And now, um, now that I passed, I can go anywhere I want. So I’ll make sure it will be somewhere very hot. So, um, to sum up, all, although it was a really difficult, really difficult challenge, I’m so glad I managed to do it. For me, it was quite an achievement, and, and I’m proud of myself for having done it.

Exercise 5

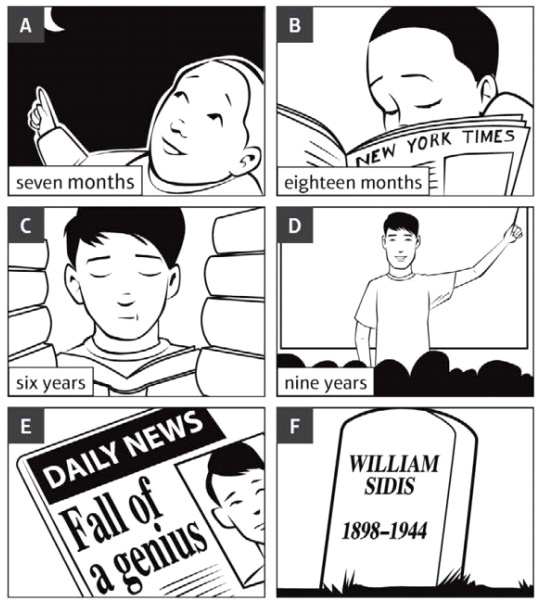

A. Pictures A—F show moments in the life of a genius. What do you think is happening in each picture?

B. Listen to William Sidis’s story and check your answers.

C. Listen again and answer the questions.

1 Where were his parents from originally, and where did they move to?

2 What was William’s first word?

3 How old was William when he could speak Russian, French, German and Hebrew?

4 What did he do at Harvard University when he was nine?

5 What did he do two years later?

6 Who “followed him around”?

7 What two things did his sister say about his ability to learn languages?

8 For most of his adult life, what was Sidis ‘running away’ from?

Answer & Audioscript

B

A When Sidis was seven months old, he pointed at the moon and said ‘moon’.

B At eighteen months, he could read The New York Times.

C At six, he could speak Russian, French, German and Hebrew.

D Aged nine, he gave a lecture on mathematics at Harvard University.

E Journalists followed him around and wrote articles about him but he didn’t achieve much as an adult.

F He died in 1944, aged 46.

C

1 His parents were originally from Russia. They moved to New York.

2 William’s first word was ‘door’.

3 William was six when he could speak Russian, French, German and Hebrew.

4 When he was nine, he gave a lecture on mathematics at Harvard University.

5 Two years later, he began attending Harvard University.

6 Journalists “followed him around”.

7 His sister said he knew all the languages of the world and that he could learn a language in a day.

8 For most of his adult life, Sidis was ‘running away’ from fame.

Audioscript

A: Sidis was the greatest genius in history.

B: William Sidis? A genius.

C: Probably the greatest mind of the twentieth century.

D: They say his IQ was between 250 and 300. That’s off the scale.

E: A genius.

F: William Sidis? Great brain, difficult life.

G: Sidis? Genius.

Was William Sidis the most intelligent man who ever lived? If so, why isn’t he famous? Why isn’t his name known like the names of Einstein, Leonardo and Charles Darwin? What can his life teach us?

William James Sidis was born on April 1st in 1898. That’s right: April the first, April Fool’s Day. His parents were Boris and Sarah Sidis, Russian–Jewish immigrants who had settled in New York. They were both passionately interested in education. Boris was a psychologist who taught at Harvard University, and Sarah used to read Greek myths to her son as bedtime stories.

It soon became clear that their son was something special. At six months of age. William said his first word, “door.” At seven months, he pointed at the moon and said “moon.” At eighteen months, William could read The New York Times. And at age three, he reached up to a typewriter and wrote a letter to a store called Macy’s asking them to send him some toys! At six, he could speak Russian, French, German and Hebrew.

All of this took place at home, but soon he made newspaper headlines. He passed the entrance exam to one of the United States’ best universities at the age of eight. Then, at age nine, he gave a lecture on mathematics at Harvard University. Attended by math professors and graduate students, this lecture put Sidis on the map. He began attending Harvard University two years later, at the age of eleven.

Now that he was in the public eye, things began to go wrong for William Sidis. The media was fascinated by him. Journalists followed him around and wrote articles about this young genius. Not surprisingly, Sidis began to feel like an animal in a zoo, with everyone watching him.

He wasn’t interested in becoming famous nor in becoming an academic. He just wanted to live a quiet, private life. He tried. He went from job to job, publishing only one book of any academic interest. But everywhere he went, whatever he did, people eventually learned who he was. And, the press kept writing about him. In 1944, he died at age 46, almost forgotten.

Since his death, many stories have been told about Sidis. Some said that his genius burned out like an old light bulb. His sister said Sidis knew all the languages of the world and that he could learn a language in a day. None of this was true. Even his IQ—which was supposed to be between 250 and 300—was just a guess. No intelligence test has been invented to go to that level of genius.

So, what can we learn from his life? First, not all childhood geniuses will produce great things as adults. They may think great thoughts or do incredible calculations, but many of them just do normal jobs and find happiness in that way. Second, Sidis spent much of his time and energy running away from fame. Unless they want to be Hollywood stars, people need to be left in peace. That’s how most geniuses do great work.

Exercise 5

A. Listen to conversations 1—3. What is happening in each one? Circle the correct option to complete the sentences.

Conversation 1

Parents are discussing a child’s ……………… .

a) behavior

b) TV watching habits

c) school grades

Conversation 2

Colleagues are discussing ……………… .

a) another colleague’s work

b) their qualifications

c) the best person for a job

Conversation 3

An interviewer is asking a question about ……………… .

a) directing a play in a school theater

b) the government’s view of education

c) lack of money for the arts in schools

B. Listen again. Which sentence do you hear, a) or b)?

Conversation 1

1 a) In my view, it’s getting out of control.

b) For my view, it’s getting out of control.

2 a) By example, she watched TV for six hours yesterday.

b) For example, she watched TV for six hours yesterday.

3 a) I’m saying that’s a lot.

b) I must say that’s a lot.

4 a) That’s not what I’m saying. She’s always in front of a screen.

b) That’s what I was saying. She’s always in front of a screen.

Conversation 2

5 a) For me, Elizabeth is the best.

b) To me, Elizabeth is the best.

6 a) For once, she has the right qualifications.

b) For one thing, she has the right qualifications.

7 a) She would, but now I’ve said that, she already has a good job.

b) She would, but having said that, she already has a good job.

Conversation 3

8 a) Yes, the reason I say this is that funding has been cut for arts subjects.

b) Yes, it’s reasonable to say that funding has been cut for arts subjects.

9 a) Let me give you an example. A school I visited last month wanted to do a play in the little school theater.

b) Let’s look at the example. A school I visited last month wanted to do a play in the little school theater.

10 a) Like I’m saying, money isn’t everything, but it’s part of the problem.

b) Like I said, money isn’t everything, but it’s part of the problem.

Answer & Audioscript

A

1 b 2 c 3 c

B

1 a 2 b 3 b 4 b 5 a 6 b 7 b 8 a 9 a 10 b

Audioscript

Conversation 1

A: We really need to stop this. In my view, it’s getting out of control. For example, she watched TV for six hours yesterday. Six hours!

B: That’s a lot.

A: It is a lot. She needs to get out more.

B: And when she’s not in front of the TV, she’s on the Internet.

A: That’s what I was saying. She’s always in front of a screen.

Conversation 2

A: For me, Elizabeth is the best. She would be really good in this job.

B: Why do you think so?

A: For one thing, she has the right qualifications. For another, she obviously really wants the job.

B: Yeah, that’s very clear. I think the other woman …

A: Kayla.

B: Kayla. She would do a good job, too.

A: She would, but, having said that, she already has a good job. You can see that Elizabeth is really hungry for this position.

Conversation 3

A = Host B = Mr. Dyson

A: Mr. Dyson, in your presentation you said that the arts in many schools weren’t getting enough attention. Can you explain?

B: Yes. The reason I say this is that funding has been cut for art subjects. There just isn’t enough money. Let me give you an example. A school I visited last month wanted to do a play in the little school theater, but there was no money for costumes or music. So, in the end, there was no school play, and the theater was closed for the whole summer term.

A: And this is a money issue?

B: I do think we could solve a lot of the problems if the government recognized the arts the way it recognizes math or science or reading, yes. Like I said, money isn’t everything, but it’s part of the problem.

Related Posts

- Practice Listening English Exercises for B1 – World

- Practice Listening English Exercises for B1 – History

- Practice Listening English Exercises for B1 – Communities

- Practice Listening English Exercises for B1 – Emotion

- Practice Listening English Exercises for B1 – Solutions

- Practice Listening English Exercises for B1 – Jobs